Coming Soon

More to “The Maybe”

There’s more to “The Maybe” than simply Tilda Swinton sleeping in a box.

It’s a curious experience to visit Tilda Swinton’s art installation “The Maybe” in its current incarnation at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA). Previously exhibited in 1995 at The Serpentine Gallery in London, Swinton – an Academy Award winning actress for the George Clooney vehicle Michael Clayton (2007), and one of the world’s most recognisable cross-over faces between the arthouse and mainstream worlds – has probably risked cynical jabs of “pretentious!” and “boring!” to present “The Maybe”, a piece that sees the blonde-quiffed actress lay more or less motionless in a glass box that shifts from room to room depending on the day. When I saw it on 19 April she was sleeping in her glass cage in a space at the top of the stairs on the third floor, a thoroughfare for museum patrons. Before that she was found in an inauspicious corner of level two, and before that I think I saw images of the box appearing in the general lobby. You just never know.

![tildaswinton_themaybe02]()

Image one source //

(Note: these official images were taken on the actual day I was there, 19 April 2013)

I stayed and watched Ms Swinton in her glass box for around 20 minutes and definitely think there is more to it than simply Tilda Swinton sleeping in a box. In fact, I think the fact that it’s Tilda Swinton sleeping in a box is entirely beyond the point. She could have been juggling in a Perspex tub or performing yoga in a hollowed out refrigerator and the effect would have been the same. The seemingly ridiculous concept of Tilda Swinton sleeping in a box is the catalyst for the art itself, which I think is actually all in the receiver’s mind. The art isn’t Tilda Swinton sleeping in a box – even if the museum plaque calls it “The Maybe – Living artist, glass, steel, mattress, pillow, linen, water, and spectacles” (thank you MoMA for using the Oxford Comma!) – but what our minds can concoct when presented with the thought of it. The concept is right there in the name: “The Maybe”. She decides when she will show up or not and, thus, forces people to contemplate art. Not only what it could mean, but right down to the very notion of “what is art”. It’s a reading that works long after the viewer as left the museum. It’s been weeks since I saw Ms Swinton in her glass box and I’m still thinking, stirring, and contemplating it. The abstract nature of “The Maybe” begins before we see it and continues long after. And I suspect the very idea of people debating the nature of art, whether they believe “The Maybe” is art or not, is at least partially what Swinton intended.

Of course, depending on how long one stands and looks as Tilda’s exhibit a whole extra dimension begins to form. There is very little to the physical presence of “The Maybe”. Looking at any motionless body for any extended period of time isn’t particularly thrilling, and so Swinton is forcing her audience to focus on the things around her. Whether its noting the white splotch of paint on her dark-hued corduroy pants, the scuffed blue and green sneakers, the tailoring of her crisp white blouse, or the pattern of oxygen bubbles in her triangular jug. What is art? Are all these elements art or is art very deliberate in its intentions?

![tildaswinton_themaybe01]()

Image one source //

Image two source //

Furthermore, my eyes drifted around the room and began to notice the other people viewing the exhibit. There are some like myself that spent more than a passing glance in the room, while others walked in – perhaps even my accident on their way to another exhibit – looked at the central installation and then moved on within the span of a minute. I noticed the people who were taking “The Maybe” very seriously and those that were treating it as a joke. I was noticing the way some viewers were worried for her well-being, while others were… not. It became a curious act of people watching – Tilda and everyone else. Again, finding art in Tilda Swinton sleeping in a glass box isn’t so much the core of “The Maybe”, but the way we react and assess and discuss. She was, after all, doing little else but sleeping. Apart from doing so in a glass box in the middle of the day in a very public setting, what about it is entirely strange? Viewers thrusting their own interpretations, much like I have here, is I think where the true intentions of Swinton’s work lies.

“The Maybe” runs indefinitely whenever Ms Swinton chooses at MoMA.

![tildaswinton_themaybe03]()

Banner image source //

Deep in Vogue with Punk’s Couture

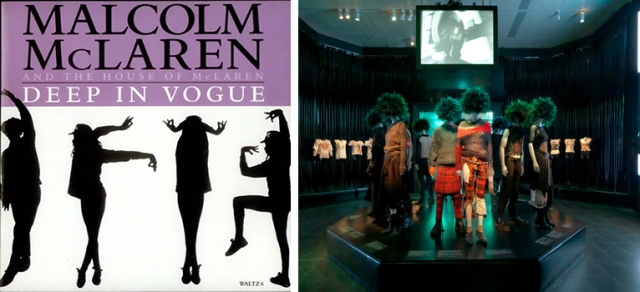

Music icon Malcolm McLaren (he died in 2010) was an integral early element in multiple counter cultures and upcoming genres throughout his career. In the late 1980s he helped spearhead the mainstream knowledge of the New York drag ball scene with his song “Deep in Vogue” that came out a year before Madonna recorded her own ode to the highly flamboyant freestyle dance concept. He was even an early figure in modern fusion of pop and opera (“popera”?) with his album Fans, and turned the rhythmic beats of street chants into vibrant and electric dance music with tracks such as “Double Dutch”, “Buffalo Gals”, and “Something’s Jumpin’ In Your Shirt”. Personal preferences aside (“Deep in Vogue”, “Double Dutch”, and “Madame Butterfly” are rather astonishing feats of divine pop), this obviously all takes a back seat to his most famous addition to global counter culture: punk.

![punkcouture_malcolmmclaren]()

Image one source //

Image two source //

The punk movement acted as a shot of revolution to the British youth population and an early seed to several different alternative cultures around the globe. Along with Vivian Westwood, his girlfriend at the time and now a famed couture fashion designer frequently worn by Helena Bonham Carter and seen in TV and movies like Sex and the City, the two turned offensive slogans and imagery into high art fashion that simultaneously enraged and engaged. The fashions that they sold in their boutique SEX on Chelsea’s King’s Road revelled in imagery of nudity and the power of language. Clothes were frequently emblazoned with images of naked men and one of the most famous, named “Tits”, is simple an image of a pair of breasts on a plain white tee. Others use words like “sex” and “rape” to evoke shock and outwardly express a generation’s contempt at an oppressive society.

All of these and more are part of the new Punk: Chaos to Couture exhibit currently at The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Quite apt that this particular museum sits on the west side of Fifth Avenue, infringing upon the boundaries of the elegantly constructed and designed Central Park since that is exactly what the punk movement did to the fashion and societal establishment in the 1970s. It infringed on a world that was so carefully designed to the idea of perfection. Depending on where you stand in the park, the museum’s architecture rises out from the leafy surrounds like a sore thumb, catching the eye of anybody walking by. It’s out of place and doesn’t belong, just like punk once did. Also like the museum, punk was eventually accepted and is now a permanent fixture and now with this exhibit is officially respected as an artistically and culturally important moment in history.

![punkcouture_cbgb]()

Image one and two source //

Entering the exhibit and you’re instantly confronted with a recreation of the dirty, muck-strewn bathroom of famous New York punk club CBGBs. It’s certainly a mood setter if ever there was one and I instantly recalled Adrian Brody’s character in Spike Lee’s Summer of Sam (1999) who performs at CBGB’s rather than the more fashionably popular discotheques and how his newfound punk persona and radicalised hairstyle is seen as a symbol of evil. A circular runway of famous McLaren/Westwood designs as well as another set recreation – this time of their SEX shop – and detailed history of their work and its cultural significance before diverting into some of the more high end interpretations of the punk aesthetic. Designers like Michael Kors, Dior, Calvin Klein, Burberry, Balenciaga, and even Chanel are present with designs that incorporate distressed materials, leather, safety pins, spikes, clips, and hooks alongside more traditional silhouettes and shapes. Westwood’s designs are clearly the more dangerous and risqué, but there’s an almost equal element of high-end danger in the runway interpretations.

The exhibition then continues along the same lines looking at how designers have taken the principals of punk and applied them to fashion that is both accessible and red carpet ready as well as experimental and avant garde (such as the garbage bag designs of Gareth Pugh).

Special mention must be made of the installation’s production design that uses grungy brick aesthetics with a stylish, slick black colour scheme. It’s a real visual treat that is in stark contrast with similar exhibits that I have seen both here and back home in Australia. The exhibition producer must be applauded for giving the display a polished, up-class look when it could have very easily been dismissed with simple white walls. More attention could have been applied to the actual music that went so hand in hand with the fashion movement, and was the reason for its rapid ascension. A few small screens playing some sort of indecipherable video wasn’t enough for my liking, nor was the lack of information and context regarding the high fashion punk looks that make up the majority of the exhibit. Minor complaints, possibly, but given the strength of everything else they are frustrating and easily fixed. Still an otherwise fabulous ode to a misunderstood and underestimated segment of history.

Punk: Chaos to Couture runs at The Metropolitan Museum of Art until August 14.

![punk_chaostocouture]()

Banner image source

The Roof is on Fire

The summer season brings with it many traditions and seasonal changes: beer gardens suddenly open up their canopy decking, gin and tonics are suddenly being ordered by far more bar patrons than usual, people feel the need to dress for summer no matter if the weather actually calls for it, and homebodies like myself start to feel a bit miserable that we can’t just stay on the couch and watch a movie on DVD or Netflix with the excuse of “it’s raining!” or “it’s too cold!” because, gee, the weather is so nice we have to utilise it (apparently). Gah!

![rooftopcinema01]()

Image source one //

However, the prolificity of outdoor cinema venues such as parks, botanical gardens, open screens (think the free screenings held in Melbourne’s Federation Square), and rooftop theatres has at least helped merge the two ideals together. Rooftop Cinema – the organisation, not the concept – have brought about a wonderful collection of films and venues to their ongoing series of films. I have been lucky to visit three times (and hopefully a few more over the next few, warm months – last week I even ended up providing impromptu volunteer work post-film) and while the festival has had to play chicken with the weather on more than one of those occasions, each time has been a delight. Even if I became a sort of communal grump and didn’t like one of the films in the face of a room of instant fans.

In fact, the one film I didn’t care for – Jordan Vogt-Roberts’ The Kings of Summer (reviewed at Quickflix) – was one that succumbed to the whims of Mother Nature and had to screen at the alternate downstairs indoor screening hall. The other two, which managed to screen upstairs on the roof without any major hitches, were rather fabulous. And one of them was even a mighty surprise given I had never even heard of it before. I sense a pattern.

![francesha01]()

Image source one //

The first feature was Noah Baumbach’s Frances Ha, the director’s second collaboration with Greta Gerwig after Greenberg. The Lower East Side screening location at New Design High School couldn’t have been a more appropriate setting for their tale of twentysomething arrested development. While the seats are not the most comfortable, given I’ve been to cafés that make people sit on milk crates (hipsters won’t be done until we’re drinking out of rusty tin cans, won’t they?) I think we can make do. The visually spectacular graffiti designs that cover the rooftop walls match perfectly with the falling sunset that falls over the city in colours of purple, pink, and orange. It’s a gorgeous setting and the cool breeze that frequently blows throw is just the cherry on top.

As for Frances Ha, the film is a delightfully spry vacation into the life of a woman who doesn’t really deserve the affectionate film around her. She’s an exceptionally frustrating woman to spend 85 minutes with, but it is to the credit of screenwriters Baumbach and Gerwig that the film itself isn’t frustrating along with it. If the film has one problem it is that’s the end doesn’t quite feel as deserved as it thinks it does, as if it suffered from that most saddening of independent film symptoms – the ending that ran out of cash (worst of the worst: Pieces of April, which literally ends mid-scene with a polaroid montage). It wraps up a little too quickly and a little too neatly for my liking just as things were getting interesting. It’s as if they had the bows, but not the wrapping paper and they just went “voila!” and let it go out half-dressed. Meanwhile, that was a bunch of mixed metaphors that I don’t even know.

The film is gloriously photographed by Sam Levy who shot in colour and altered it to black and white in post-production. It lends the film a crisp look that is entirely bewitching. Whether they deliberately wanted to evoke Woody Allen’s 1979 masterpiece Manhattan (my personal favourite Allen film) or not I’m not sure, but the film’s beguiling monochrome vision of New York – Manhattan and Brooklyn for the most part, plus it was nice to see Washington Heights get a piece of the pie – does just that. Jennifer Lame’s brisk, tightly-executed editing certainly helps things immaculately. And, of course, Gerwig is a breath of fresh air as she inevitably always is, reminding me of other steadfastly indie queens Chloe Sevigny and Parker Posey, but with the awkward wit of a Julia Louis-Dreyfus.

The Dirties a few weeks later was a pleasant surprise. “Pleasant” in the ways that a film about a school shooting can be, I suppose. Despite the prickly subject matter, Matthew Johnson’s debut feature is an energetically made and comically tense navigation into the motivations and building scale behind a school shooting. It’s fresh and original and utilises the popular trend of mockumentaries to watch a horror unfold in an entirely different and unique way. If the film wasn’t such a DIY effort from the production team then I might have been worried that the screenplay was suggesting a link between film and the enacting of violence, but I think the filmmakers do a very good job of suggesting that the lead character of Matt (as played by the director) was clearly unstable before any of this was set into motion. “Movies don’t create psychos, movie just make psychos more creative”, as one famous movie once hypothesised (that movie was another high school massacre movie, but one of a decidedly different nature, Wes Craven’s Scream.)

![thedirties_banner01]()

Image source one //

What the film isn’t shy about, however, is its linking of teen bullying to acts of violence. Whereas Gus Van Sant’s Elephant tried to skirt the issue and present it in very black and white terms (although suggesting everything from bullying to homophobia to video games to incessant piano concertos), Johnson makes no qualms about suggesting that school corridor bullying is to blame. That the end throws an ambiguous, atypical curve ball is a credit to the director and adds another layer of teen mythos to the oft told story of gun-toting boys that has been examined in films Polytechnique (another Canadian production), 2:37 (the Australian film that blatantly ripped off Elephant) and Home Room.

I admired the film for inserting a sense of humour to the project, without which the film surely would have suffocated under the dire low budget aesthetic. It doesn’t make jokes about school massacres, but merely has funny characters at its centre. It’s actually refreshing to see core characters of a story such as this not represented in the typical fashion. Like so many bullied children, Matt and Owen try to make their rather miserable existences as bearable as possible by wrapping themselves up in a world of laughter. And while Matt’s sexuality (or, non-sexuality as it actually seems) isn’t directly brought up, it’s quite obvious that he’s a homosexual (the film is set in 2001 and he has posters of The OC‘s male cast hanging on his wall) and I found that just another bonus layer of intrigue in this fine film.

While the sold out audience that greeted Frances Ha was hardly surprising (especially so with Baumbach and Gerwig in appearance for a decidedly awkward Q&A afterwards), it was wonderful to see the seats packed for The Dirties, too. The lively Q&A was a delight too, and kudos to whoever at Rooftop Cinema is in charge of hiring the pre-film music accompaniment since the bands selected have been top notch. Brazos at Frances Ha, Bird Courage at The Kings of Summer, and Hani Zahra at The Dirties. Not only that, but they typically fit quite well with the films they preceded. And if music and a movie in a wonderful location weren’t enough (there are multiple locations across the boroughs, but I haven’t had the chance to experience them yet), there is always an after party at a bar around the corner called Fontanas where, if you’re lucky, you can score three or four free beers. Pretty good for less than the price of a movie ticket at AMC.

Rooftop Cinema have some excellent product coming up soon including screenings of Ain’t Them Bodies Saints, Central Park Five (a free event on Tuesday the 18th), Crystal Fairy, Towheads, and a selection of short programs that are heavily focused on New York City, as well as a highlights package from this year’s Sundance Film Festival. A full look at their schedule can be found at their website.

![rooftopcinema01]()

Banner image source //

Across 110th Street

Just because the area of Central Park north of Jackie Onassis Reservoir may not be as famous or well-traversed – it’s certainly not for filmmakers – doesn’t mean it wants for a beauty all its own compared to the southern region and The Ramble, more popular with city-dwellers and tourists alike.

Beginning at 110th Street, Central Park’s northern tip is instantly striking. The flat lawns to the left make way for the rise of its mountainous walking trails that are famous for birdwatching. A sign informs me that over 200 species of bird either make the area their home or use it is a migrational stop (the rest of the park works in much the same way, but in less of a compacted fashion). When trekking this rocky segment of the park it is easy to forget that Central Park isn’t just an escape from the clichéd hustle and bustle of the city (why you would move here if you don’t like the aforementioned hustle and bustle is beyond me), but an escape from everything. If it weren’t for a news helicopter flying overhead you’d be forgiven for forgetting that you’re right in the middle of an island with three million occupants.

It’s easy to find a spot anywhere in this section of the park that is ideal for quiet, even contemplative relaxation. The constant chirping, whistling, and cooing trills of the wildlife mix perfectly with the beautiful surrounds that come in multiple shades of green. I found a rocky resting place on The Cliff outside the oldest building in the park – the Blockhouse, built in 1814 – which can be seen here.

From there one can head to a spot known as The Great Hill. Described by the Central Park Conservatory as “open hilltop meadow” that was once used as a viewing point for carriage riders to view the Hudson River that had eventually vanished due to tree growth. The area has had a remarkable transformation from its lowest point in the 1980s when it had been deserted and dilapidated, but which now hosts picnics, joggers, outdoor theatre and cinema events, as well as art workshops. The large expanse of space on the early-afternoon time that I visited was occupied by little more than a few lounging workers on a lunch break (the suit jacket over the back of a bench would at least imply that), book-reading sunbakers, and one attention-grabbing tourist couple who decided to throw around a frisbee in the barest minimum of clothing allowed in a public place frequented by families.

From there the region is a series of tree-lined paths. There’s a curious amount of joy that comes with discovering a tucked away cubbyhole that looks as undiscovered as you’re likely to find in a place such as this. On this warm 26-degree day (that’s a fraction under 80 degrees Fahrenheit) it remained quiet and gorgeous.

The true ace in the hole of Central Park’s north, however, is a blissfully tranquil and stunningly gorgeous area known as The Pool. Surely the most under-utilised gem of Central Park’s mass design. The trick is to find your own little nook and indulge in the splendour of the grass (so to speak). I found a smooth rocky formation on the edge of the pond mere metres away from the ducks gliding on the surface, the willow tree dragging its limbs across the rippling water, and even a romancing couple sharing a glass of afternoon wine.

It’s like a scene from The Wind in the Willows if you ignore the group of cyclists, football-throwing college students, and the menagerie of accents that populate an areas such as this in a city like New York. It proves that there’s always much

Continental and The Secret Disco Revolution Examine Gay Culture’s First Blush with Mainstream

“In order to be successful, you either have to create a desire, or fulfil a need”, says Continental bath owner Steve Ostrow in writer/director Malcolm Ingram’s third homo-centric documentary Continental (after Small Town Gay Bar and Bear Nation). “In this case, it was doing both.” The latest in a recently extended line of documentaries examining less mainstream elements of gay culture history – I Am Divine and Before You Know It are two others to came out of this year’s SXSW festival – Continental is a conventionally assembled, but briskly entertaining recounting of how what is now considered a hush-hush underground aspect of gay life was at one time an open secret and hive of activity. It gave birth to the fame of Bette Midler and Barry Manilow alongside allowing New York gay men an outlet for their sexuality that society was determined to supress.

The Continental Baths being what they are (homosexuality was illegal when they first opened), very little video footage exists and so Ingram relies more on still images, generic pornography footage, and New York stock footage with old film reel filters overlayed – one specific piece of vision that is frequently used initially looks like it could have been filmed in the 1970s, but actually has the new World Trade Center in its sight. It doesn’t necessarily work against the film per se, but it does mean the film has to fall back on less interesting documentary tropes like recurring talking heads and reoccurring footage of the hotel that housed the baths.

![continental_tee]()

Image Source //

As a result, the film works best when simply recounting its sordid tales in refreshingly frank openness (we can thank Michael Musto a lot for that). Its examination of the bath scene of the ‘70s is illuminating and results in a film that is probably as close as we’ll ever get to looking at this period in great, specific detail. It should certainly be a must see for anybody interested in queer history. Whether you’re a gay man who supports these places or not (I’ve personally never been, but gay men have so many more avenues nowadays for obvious reasons), they played a large part in the story of gay culture’s blending with the the mainstream lifestyle of the time. At least in New York City, anyway. Ostrow and his former employees recount some wickedly entertaining stories from the day, including the mafia, the disco, and most importantly the Continental’s brief period as a celebrity go-to location. Apart from homosexual celebrities Andy Warhol, even Johnny Carson and Alfred Hitchcock went there (not together, obviously)!

Famous for Ostrow’s championing of disco and opera, as well as their elaborate cabaret shows that introducing Bette Midler and Barry Manilow to mass pop culture, and on through to their part in the spread of AIDS (the Continental itself, however, closed down several years before the crisis struck New York in the 1980s), which was a specific plot point in excellent 1993 TV movie And the Band Played On, Continental remains an interesting study. Ostrow, permanently wrapped in a scarf, is an entertaining personality to pivot a documentary around and it could have been interesting to have investigated more into his personal life (although an operatic coda at film’s end is a nice way of bringing things full circle).

![continental_opera]()

Image source //

Much like the baths, disco music had itself a brief heyday during the 1970s when sexual liberation was the next frontier. Jamie Kastner’s documentary The Secret Disco Revolution aims to reposition the conversation of disco music and its legacy into its rightful place: that of a revolutionary and exciting time full of brilliant talent producing music that is – just like pop music today – criminally underrated. However, as well-intentioned as this movie is, it is not as well made nor as well-assembled as Continental. Ingram’s documentary was wise to focus on the one location and not any of the other baths that were prevalent at the time (The Meatrack and The Anvil for example), but The Secret Disco Revolution takes a far too broad look at its subject and inevitably comes out looking less than comprehensive.

While there is plenty of interest in Kastner’s documentary, anybody with more than a passing knowledge the disco era will know most of it already. Especially as it pertains to personalities such as Donna Summer (sexually exploited by her years as one of Casablanca Records’ golden goose) and The Village People (some of who still don’t see the incredibly homosexual undertones of their music). The latter group with their flamboyant costumes and catchy disco pop hooks were, as the film shows, somewhat unwitting pawns in their producer’s desire to inject a post-Stonewall homosexual sensibility to mainstream heteronormative culture. Furthermore, the film is more interesting when navigating the tricky critical and cultural reception to disco music, including the famous album burning events at sport stadiums, which personify a sort of homophobic intolerance to what disco music was doing to masculine radio stations across the country.

![secretdiscorevolution]()

Image source //

Interspersed with rather embarrassing sideshow of three disco revolutionaries (I don’t even know) and a disappointing lack of extended time capsule footage (there’s plenty of it, but only in mini glimpses), The Secret Disco Revolution sadly doesn’t do enough with its subject to succeed. Disco is such a glamorous and exciting era of music and it deserves better treatment than this only fleeting entertaining documentary. It’s a film for disco die-hards only, and they will presumably be as ho-hum about the affair as I am. Compared especially to Continental, The Secret Disco Revolution only makes the former look more impressive. Continental: B; The Secret Disco Revolution: C-

Continental plays BAMcinemafest tonight in Brooklyn.

The Secret Disco Revolution is on VOD and in cinemas on 28/06/13

![continental_banner]()

Banner image source //

Snow White’s Sadistic Sister

If one is to view Paul McCarthy’s latest large-scale exhibit at the Paul Avenue Armory as a treatise on the mass corporatisation of Disney then, well, he must hold them pretty low esteem. With “WS”, the 67-year-old Californian artist has combined long-form video, intricate interactive sets, and lifelike model work into a sort of hardcore phantasmagoria that defies explanation. McCarthy’s installation has set up shop in the massive former drill hall on Park Avenue and is made up for two wide-length cinema screens, multiple sideshow rooms, extra viewing platforms, school desks for seating, as well as the set on which the over 7 hours of film was staged. Amongst the set is a house that all but reeks of rotting food and sexual depravity – art directed to within an inch of its life, no doubt – and an excessively fake forest illuminated by green, red, blue, and yellow spotlights.

McCarthy has taken the story of Snow White and the seven dwarves and morphed it into something akin to Harmony Korine’s Trash Humpers. Filled with perverse sexual acts and pornographic representations of pop culture idols, it’s certainly an unconventional way to spend several hours. The scale of the piece would require at least two full days to take it all in. I spent roughly four hours attempting to take in McCarthy’s warped vision and that still feels extravagant. The video portions of the piece are repetitive and numbing in their oddness. I appreciated some, couldn’t comprehend others.

![whitesnow_screens]() Image Source 1 //

Image Source 1 //

McCarthy himself plays a character called ‘Walt Paul’, which could only be misinterpreted by squirrels. He wields a sadomasochistic knife over the proceedings like a maniacal puppet master. “Neither daughter, sister, no friend”, he tells White Snow. “You shall be no more than my slave.” You can see where this is going. While the story follows that of the 1937 to a degree, it eventually descents into a free-flowing near plotless collection of fetish fulfilments. White Snow, played by Elyse Poppers – she has a small acting career with video game voice work and short films credited on IMDb – covers her face and body with food (Walt soon joins in), experiments sexually with all sorts of acts and fluids, and desecrates the famous red, blue and yellow costume that is White’s signature. Meanwhile, the dwarves with their comically bulbous artificial noses, who, from what I could tell, were not all played by short-statured actors, hi ho hi ho their way off to work during the day wearing sweatshirts of UCLA and Yale, before coming home to a sty of filth and depravity.

The video sideshows take place in inter-connected rooms off to the side of the Armory’s main stage. They feature more food-related video, but most predominantly feature a sub-video called “The Prince Comes” in which three male porn actors masturbate in the forest before having sex with a lifelike body form (a prop which is displayed in a glass cabinet outside). It’s incredibly odd, and only fleetingly arousing, especially since the high-pitched snow motion soundscape from next door bleeds into it.

The set of the Armory is decorated in carpets sourced from Disneyland hotels with ornate patterns that only occasionally intersect, which I guess is a good metaphor for the show in the way it only fleetingly intersects with the original source material. As a highly sexualised take on the material – upon entering the building there are multiple signs signally its adults only nature – I guess it works as a kin to the gloomy Snow White and the Huntsman and the cartoonish Mirror Mirror. It’s a take that certainly just as valid as those two recent cinematic interpretations, although I found it just as successful as the former (I am actually a very big fan of Tarsem Singh’s Mirror Mirror). That McCarthy wanted to subvert the material is obvious, but the execution is frequently frustrating and unfocused. Perhaps a tighter reign could have made it more successful, but I certainly can’t picture many people finding the stamina to stay for the entire opening hours.

![whitesnow_sprinkles]() Image Source 2 //

Image Source 2 //

The show features many of the hallmarks of being pretentious and those who struggle with more outré art will not only find much to dislike, but outright hate. Many will be disgusted and will find its bombardment of sexual imagery, especially when it utilises just famous child-friendly property like Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, off-putting. I can’t disagree with them, although I did find myself eager to try and seek out a meaning beyond the obvious. I’m not sure I came across one, but it certainly provoked a lot of thought from me so perhaps McCarthy succeeded if his mission was to merely confound and make people consider the way we ingest mass culture. One could call it a nightmare vision, but that would imply that anybody other than McCarthy could have come up with visions such as these awake or not.

Throughout I recalled the likes of Andy Warhol, David Lynch, Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s Querelle, and Guy Maddin’s Twilight of the Ice Nymphs. If one cared to partake in seven hours of the project then it’d be recommended they alternate between the main feature and the side shows. The various viewing platforms also aid in making the repetitive footage more palatable over the longterm. I admired its scope and its ambition and I definitely recommend the show to anybody who wants to experience something very much out of the ordinary, but it’s also not entirely wrongheaded to wish this time-consuming has something a bit more substantial to offer. If little else, one likely won’t look at cheese slices the same.

![whitesnow_sets]()

Banner Image Source 1 //

Liberace and Anna Nicole: Larger Than Life on the Small Screen

Television has long been fascinated with telling the life tales of famous personalities. These personalities that lead lifestyles with a mixture of fabulous and tragic tend to fascinate with the excess and the desire and the wish fulfilment, while also hinging on the fact that they tend to die either young, or tragically, or frequently both and, well, that life in suburbia doesn’t look quite so bad when you figure that. Still, it’s curious that two of these larger than life personalities should not only get granted made-for-television biopics within weeks of each other, but that they’re both made by directors with considering talent and clout. It’s a shame then that only one rises above its kitsch trappings.

Steven Soderbergh’s supposed final feature project (but who can tell, really?) is Behind the Candelabra about closeted piano player Liberace. Despite the presence of Soderbergh behind the camera and Richard LaGravenese behind the page, Candelabra is a surprisingly straight-forward biopic. While Soderbergh grants the film a lush, shiny surface on which to hang the drama, it’s a shame that he and laGravenese kept the material so rote. The first hour is incredibly entertaining, full of vivid character portrayals and fulls of sets and costumes that sparkle both literally and figuratively. It’s sad then that it becomes so fixed into A-to-B-to-C style structure that it begins to suffocate. Its final passages, as well acted as they are, lose potency and, thus, the intimate power that Soderbergh was obviously striving for. At least it remains a keen, sly sense of humour. I suspect I’ll be chuckling about Rob Lowe and the absurdity of Liberace wanting his younger lover to get plastic surgery to look more like him long after the credits rolled.

![behindthecandelabra_douglas]()

Image source 1 //

Behind the Candelabra was screened in competition as this year’s Cannes Film Festival and will also be released theatrically in some international territories (Australia, for instance, next week). I would have liked to have seen it presented on the big screen because I suspect many of Soderbergh’s images (he again has enlisted himself as cinematographer, credited as “Peter Andrews”) would look divine on the big screen as devoted to mirrors, silver, and rhinestones as he is. Still, perhaps knowing that the project was first and foremost a HBO television movie curbed his creativity. There were visual and editing decisions made in the opening and closing minutes that reminded me very much so of Bob Fosse’s All That Jazz, but little else.

One of his strengths is in the way he subverts traditional narratives and finds interesting moments that other directors wouldn’t think twice about. He finds that here with the stunning near-silent performance of Cheyanne Jackson (Soderbergh has always been a master of the background actor) and the opening sequence inside a gay bar to the pulsating beat of Donna Summer’s gay anthem “I Feel Love”. But the second half feels bereft, like it’s going through the motions of what a television biopic should be. I’m hesitant to call it rushed, but it certainly feels more like he knew he had to cover certain moments above anything else, knowing he had to fit his film comfortably within a two hour time slot on a Sunday night. Consider Erin Brockovich and the way it covers a very traditional narrative by also finding moment smaller moments with its characters that help build into a more dynamic whole. I found that missing with Candelabra’s second half and it hampered my overall enjoyment of the film.

That’s a shame considering there really is a lot here worth celebrating. If nothing else, it’s nice to see Soderbergh embrace the material and not dumb down the sexuality or the flamboyance of its characters. Unlike some high profile films about gay characters (hi Philadelphia!), the two men at the centre of Behind the Candelabra are very open about their sexuality and their desires (even if they can’t be on the stage). There’s no mistaking it, and Michael Douglas and Matt Damon do a wonderful job in making their unconventional romance, with all the excessive Las Vegas sheen that it’s dipped in, feel true and genuine. When the two share a hottub or lie in bed, Soderbergh’s camera watches it and truly allows their bodies to be seen and identified as together. That’s a side of Soderbergh I’d never seen before. He’s shown characters be sexual before, sure, but the way these two men are portrayed is different. There’s a simplicity, a matter of fact frankness, to it that I liked. Much was made of the film’s Australian MA15+ rating (it has since been downgraded to an M) and I can’t help but suspect it was because these two characters are sexual and enjoy it. And even in the face of the AIDS disease that eventually claimed Liberace’s life, there’s no regret in what they shared.

![behindthecandelabra_damondouglas2]()

Image Source 2 //

Elsewhere the performances from the likes of Rob Lowe as a wonky-faced plastic surgeon, the aforementioned Cheyanne Jackson as a jaded protégée, Debbie Reynolds as Liberace’s mother (how’s that for casting!), and Bruce Ramsay as a sexualised houseboy fill a typically sublime Soderbergh ensemble that also includes Dan Aykroyd, Scott Bakula (with one helluva moustache), Nicky Katt, and Paul Reiser. Ellen Mirojnick’s costumes are spectacular from Liberace’s elaborate stage outfits to the humorously slothful robes and caftans of his home wardobe, as is Howard Cummings production design with its ability to be at once ornate and vacuous.

I would have liked further examination of Liberace’s relationship with the public since it was such a defining part of his life. There’s a wonderful exchange early on between Damon and Scott Bakula who are attending a Liberace show when the two share their shock at audience’s not being aware that the piano-man is a big ol’ queen, only to have an old lady in front turn around and scold them with her eyes. Given the events that dominate the film’s second half – the relationship divorce, AIDS scandal that they didn’t want to admit – were so because of Liberace’s desire to not be known as a homosexual, I thought it was one aspect that could have been heightened and given the drama an added edge.

If Soderbergh’s Candelabra can’t keep its larger-than-TV ambitions going for the entirety of its runtime, then Mary Harron’s Anna Nicole never even attempts it. It’s a deflating experience to be sure given Harron is responsible for one of the greatest films of the ‘00s and had at once stage looked like she was set to become a defining name of the American independent cinema scene. Sadly, like so many female directors of her era (see also Patty Jenkins and Kimberley Pierce) the strange career that has befell her (I couldn’t even finish her vampiric YA adaptation The Moth Diaries) now sees her direct this lifeless biopic of Anna Nicole Smith. While the subject matter is actually a very interesting one, and something that would suit Harron perfectly given her history of looking at maligned figures in a clear-eyed fashion, she has unfortunately been laboured with a disappointing screenplay that does little to turn Anna’s life into anything but a string of typical tragic rags-to-riches clichés. There’s the deadbeat mother, the babies, the drink, the romance, the court-wrangling. No matter what Harron may or may not think about Anna Nicole, the screenplay by Joe Batteer and John Rice doesn’t see her life as noting but a cliché.

![annanicole_agnesbruckner]()

Image source 3 //

I have little down that Harron could have worked the material into something unique if she wasn’t beholden to the usual tropes of a “TV movie”. There’s no personal stamp whatsoever on this project and if I hadn’t have known she’d directed it I wouldn’t have had any reason to believe the director of American Psycho and I Shot Andy Warhol was behind it. To be perfectly honest, given the great strides that television has made in usurping cinema as the go-to moving image artform, it’s even more disappointing that nobody would let her do it. The subject matter will pull in the curious gravewatchers no matter what, so why not allow her to go somewhat less traditional? Unless, of course, they did and then Anna Nicole is a sadder state of affairs than I initially feared. Harron tries what she can to inject the material with energy where she can, whether it’s in the colour of her costumes, the oddness of a scene clad in clown make-up, a surprising camera angle here or there, or with Agnus Bruckner’s committed performance, but the material (and the Lifetime home) just doesn’t permit her enough of a home to do so.

Where Harron and the film does succeed, however, is in treating its subject with due respect. The film seems obvious worth in Anna Nicole’s climb out of lower class squalor and it is never not on side with her, treating her like the trash that so many around her did. If anything, it takes the stance of her octogenarian husband played here by an affective Martin Landau of sympathetic admirer. It’s just a crying shame that a film about a person with so much lust for life isn’t itself as vibrant. To some, Anna Nicole Smith was a breath of fresh air, a bombshell who was smart enough to know what she needed to do to get ahead, but the film is stale and shows none of the ambition that was so important to its subject.

![Matt Damon in Behind the Candelabra]()

Banner image source 1 //

Dwan Six Times: The Rise and Decline of a Director

I consider myself fortunate to have been able to see six films as a part of the Museum of Modern Art’s recent Allan Dwan retrospective, “Allan Dwan and the Rise and Decline of the Hollywood Studios”. Naturally, in retrospect I wish I had seen more, but given I was initially not planning on seeing any of the films I’m glad I got to see any at all. It was, in fact, a visiting friend of mine who convinced me to see one, the 1927 silent drama East Side, West Side, and I enjoyed it so much - so much! - that I stayed for the second Dwan feature that evening. I’d intended to see more, like Tennessee’s Partner, The Woman They Almost Lynched, The River’s Edge, and Sands of Iwo Jima, but various things got in the way.

Considering the six films that I did manage to catch, it actually appears to be quite a fair representation of his career. Of course, given he made over 400 films (and you think Woody Allen is prolific), six rather a pitiful number, but when the Canadian director who was nearly 100 when he died in 1981 is seemingly never mentioned by anybody anywhere, I think six is probably more than most people can claim. Well, except the MoMA regulars who I often heard boasting of having seen them all. I got to see some of his vibrant and visually arresting silents, his attempts at Hollywood epic, a decidedly B-grade attempt at the popular western genre, and the two oddball final films that provide an almost sad coda to his career as someone who Hollywood appeared to have given up on. I’ve got a perspective on the man and with his name now on my radar I can only hope that I get to see more of his work.

![eastsidewestside_lobbycard]()

Image source 1 //

The first and the best was East Side, West Side, a 1927 silent drama that Dwan also wrote based off of a novel by Felix Reisenberg. It’s curious that this film isn’t cited for often as a definitive “New York movie”. Not only does it so beautifully capture the city – the MoMA notes even hail his “excellent use of New York locations” – but it tells a rags-to-riches tale that is so indicative of the NYC spirit. The city in the 1920s is spectacularly rendered (although certain dramatic events suggest it may in fact be set in 1912) on screen by Dwan and cinematographers Teddy Pahle and George Webber, helped by what I think was actual real location work, that I was captivated from the get go. Its first ten minutes set along the Manhattan waterfront are truly some of the most visually arresting images I’ve yet seen projected. That they feature the exceptionally handsome George O’Brien (better known for Murnau’s Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans) certainly helps, but the images of a sleeping New York as a barge makes its way down the foggy East River under the stars of a skyscraper skyline would be enthralling anyway.

O’Brien’s immense physical presence certainly makes the ensuing drama understandable. Once washing up onto the shore and attempting to avoid getting embroiled in a street fight, O’Brien’s John Breen himself in the company of a lower class family of the Lower East Side and later becoming the surprising protégée of a wealthy west side architect. The nondescript nature of his name, John, means it fits into both; the working class and the upper class and his likeable persona certainly means he finds friends fast. He begins working in the tailoring and suit shop of his east side adopted family and eventually puts his hulking frame to use as a boxer. He’s soon enough swept up in the lifestyle of a man who believes himself to be John’s father and begins to get involved with the man’s daughter (which, yes, implies incest that the film curiously doesn’t broach the top of). Extra note: you wouldn’t want to fall asleep during this movie, especially as the film takes a very strange detour in recreating the sinking of the Titanic at the start of the third act. One could find themselves very confused. The (shall we say fabulous) German (below) and Spanish marketing campaigns even went so far as to retitle the film as Titanic even though that focus boat is never actually mentioned by name and the sequence comes maybe an hour into a story that previously completely sidestepped the Titanic. The more you know!

I adored the film from a visual stand point, with its breathtaking images and smart use of framing. Where Dwan’s film really surprised me was in the very modern vibe of the picture. None of the actors are guilty of hammy over-dramatised stylisation that silent films can sometimes suffer from – everybody here feels very natural, which helps it connect more emotionally than as just a visual pleasure. The use of real locations also keeps it grounded, and connected to a world that very much still exists today. The hurried rush of the LES is still very much alive and thriving albeit as a more gentrified entity, as is the more luxurious qualities of the Upper West Side. East Side, West Side is very much a movie about, as the poster states, “New York today with its loves, passions and hates.” I suspect many people who feel they can’t engage with silent pictures would certainly appreciate this one. If little else, they can certainly admire the scenery.

The scenery in Stage Struck is the one and only Gloria Swanson. A film of delicate humour that had be frequently laughing out loud, but which never descends into outright slapstick. Again, for a film made in 1925, Stage Struck feels decidedly modern. It’s paced exactly right and its cast have keen timing. Dwan isn’t a particularly fussy director and nowhere is that more suited that here. The material does all the work necessary and many contemporary directors of comedy could take a lesson or two from the way works a joke and then moves along to the next one rather than hovering around like a vulture. Fun fact: Stage Struck was at least partly filmed at the Kaufman Studios in Astoria, NY, which is literally about five blocks from my apartment.

With Stage Struck I saw that Dwan was a perfectly fine director, but figured maybe it’s the projects with bigger scopes that see him bring out the directorial bells and whistles like what I’d seen in the sprawling character study of East Side, West Side. These two faces of Dwan were on display, I felt, with the next two features of his that I watched. The 1938 African-set epic Suez and the 1954 western Silver Lode.

![suez_poster01]() Image source 2 //

Image source 2 //

The former tells the story of the building of the Suez Canal with Tyrone Power as Ferdinand de Lesseps. All the hallmarks of Hollywood epic are there – the love triangle, the exotic locale, the dramatic setpieces, the grand history of it all – and when given the chance to do so shows Dwan as a very strong director. Nominated for three Academy Awards – I’m not sure of many Dwan films that can claim that - Suez is rich and grand, with a centrepiece sequence involving a highly destructive sandstorm making a great impression. He’s unafraid to shun sentimentality for the all too real circumstances of death, especially involving one character whose exit is unexpected and emotionally quite affecting.

However, Suez is the first of the films I saw that had Dwan actively trying to keep up. This was surely an epic for him, but it’s still a rather small picture. Dwan’s direction is impressive and he has utilised whatever budget he had well, but I can sense the almost blue collar sensibility in him at work. Whereas his silent work felt new and bold and vibrant, Suez appears to find the director working harder than ever to impress and making the type of film that was dictated by the times. He was never a director that would have had his pick of major motion pictures, but when given the chance to work on something such as this he could be guaranteed at providing a winner.

By the time Silver Lode came along, however, nearly 20 years later Dwan was into his fifth decade as a director and in very much the twilight phase of his career. One can forgive the man for perhaps going soft of the pedal and Silver Lode is a perfect example of the sort of solid entertainment, not quite A-list films that he was churning out. I’d initially not responded all that well to Silver Lode, considering it solid but unremarkable. And while I still don’t consider the film, an 81-minute western set on July 4th Independence Day, to be all the best of what I have seen from him, I’ve found myself thinking about it more than any of his other works.

![silverlode_poster]() Image source 3 //

Image source 3 //

I appreciated the film’s screenplay more than anything, to be honest. While there are lapses in logic – those townspeople, oy! – I appreciated its single day structure, the protest to McCarthyism, its surprisingly adept female roles, and the no fuss way it goes about its business. It’s lean and more than a little mean, if you catch my drift. I actually think the actors are more or less fabulous, with particular notice going to Dolores Moran and Lizabeth Scott as two very different small town women. Cinematographer John Alton had won the Academy Award some years earlier for An American in Paris, and while the film doesn’t often allow him to really do much with the frame, there’s at least one shoot-out sequence, done all in one take as Payne’s falsely accused gunman criss-crosses across down hiding behind any objects he comes across, that is superb, stunning work. It’s a moment of alchemy between the camera and the set and really highlights the film’s excellent formal work all around.

Silver Lode is like comfort cinema of a sort. It has so many ingredients that make for an entertaining film that it’s almost impossible to not get at least some enjoyment out of it. It’s lazy Sunday afternoon fare, the type that one could come across on the ABC (Australia, not USA) one day and there’s something really sweet and old-fashioned about that. I’d certainly leave it on if I ever spotted it while channel surfing.

There’s definitely a streak of paranoia running through Silver Lode, which makes it an intriguing property to look back on. What I had initially thought was a fob off from Dwan turned out to be a film very much keeping in with subjects he liked to tell. He made other westerns, including one with Ronald Reagan that I unfortunately had to bypass, but I’m not sure any of them would have such an overt reference to the McCarthy communist hunt. The villain of Silver Lode isn’t called Ned McCarty for nothin’, you know.

![mostdangerousmanintheworld_poster]() Image source 4//

Image source 4//

This political edge would extend on through to The Most Dangerous Man in the World seven years later. What would prove to be his last film – he simply retired, having presumably exhausted himself making so many films one right after the after – this 1961 curiosity is a fairly standard B-movie about the dangers of nuclear war that is fairly typical of the era. By this time cinema had well and truly moved on and Dwan was making the type of movies that would be the el cheapo second film in a double feature. The Most Dangerous Man in the World lacks almost all the finesse and beauty of the earlier films I had seen, but at least the man still knew how to adapt. He doesn’t disguise his films as anything that they’re not. This is cheap science fiction, and there isn’t necessarily anything bad about that.

The last film I saw from the retrospective was actually the second last feature he made. From 1958, Enchanted Island is easily the weakest of the six. The only film of his that I saw that I would say is actively bad, it’s a poorly-acted desert island flick that suffers from production values that run from average to poor and performances by the likes of Dana Andrews and Jane Powell that lack charisma. The tropical locales look divine, but that’s window-dressing for a film that’s otherwise casual with its racism (a white actor portrays a tribe leader who’s obviously meant to be of Polynesian descent) and misogyny (“hahaha!” laughs Andrews’ jungle seaman as he throws a fishing net over his exotic girl-wifey, to which the woman’s father responds “He can keep what he caught!” before she gets slung over the brute’s shoulder and shipped off to the jungle).

“He dared to love a cannibal princess!” reads the poster, which is ridiculous. The film’s cannibal subplot only ever briefly flirts with being interesting, and then is mostly discarded as a humorous misunderstanding between cultures. This is the bad kind of fluff, shamelessly glowering at a culture different from our own, but dressing it up in pretty colours to mask any off-putting sentiments that audiences may accidentally pick up on. At least Allan Dwan got to make one more film after this – curiously three years later, the biggest gap between any two Dwan features – but this was a decidedly off-colour end to my first experience with Dwan.

![enchantedisland_postcard]() Image source 5 //

Image source 5 //

I can definitely see why MoMA decided to do the retrospective. He’s a director that typifies a lot of what Hollywood was doing in its first half-a-century of existence. He is an example of somebody that perhaps never quite had the goods to go all the way to being hailed as a filmmaking legend, but who worked with what he had perhaps more than anybody else. If the initial promise of his early years (and, to be fair, even by 1925 of Stage Struck he had already made over a hundred films beginning in 1911) didn’t quite continue on through the decades, then he’d hardly be the first director to do so. A consummate professional who tried to do his best with whatever he was given even when it included shrinking budgets and an industry that was in the early stages of moving away from the types of films he was best at, and who made movies clearly because he loved cinema above all. Viewing these films was illuminating and eye-opening and I’m grateful I got to see them. I’d be willing for the retrospective to keep going more months on end just to give me the chance to see them all.

How Do You Solve a Problem Like Gender Inequality?

“It’s about time”, said Barbra Streisand at the 2010 Academy Awards before announcing “…Kathryn Bigelow” as the first female winner of the prestigious best director prize for The Hurt Locker. Given the then 67-year-old multi-hyphenate’s own chequered history with gender inequality with the notoriously lady-shy director’s branch, she’s surprisingly not bitter. Her lack of a nomination for Yentl in 1984 was met with heated debate and even protest for its perceived sexism, and furthermore in 1991 when her film The Prince of Tides found itself in the unlucky position of being a best picture nominee minus its director to which host Billy Crystal famously quipped, “did this film direct itself?” Despite that, and despite her own famed vanity (lest we forget The Mirror Has Two Faces), she’s always been pro-gender equality and I adore what she said at the 65th Academy Awards in 1993 before announcing that most manly of men, Clint Eastwood, the winner:

“Tonight the Academy honours ‘Women and the Movies’. That’s very nice, but I look forward to the time when tributes like this will no longer be necessary. It won’t be necessary because women will have the same opportunities as men in all fields. And will be honoured without regard to gender, but simply for the excellence of their work. A time when there couldn’t possibly year a ‘Year of the Woman’ because there will be so many in prominent positions.”

It’s inarguable that women still face tremendous uphill battles in the “biz” of film and television, with the latter definitely showing vast improvement in recent years both here and abroad (so many fabulous women on TV that the Emmy categories are literally overflowing). Newly released data out of England states that only 7.8% of British cinema was directed by women last year. That’s a diminishing of 50% and a startling figure. Similarly in America, the oft-cited statistic is that women make up 50% of all film school graduates, and yet make up a paltry sub 20% of directing positions. Depending on where you look, the figures tossed out look at one female director for every 15 male directors, 5% of the top 250 grossers, and so on.

And not just directors, but nearly every other position of filmmaking ranging from acting to screenwriting to cinematography. The only fields in which women traditionally dominate are “crafty” fields such as costume design and make-up. The only women to win Academy awards in gender non-specific categories at this year’s Academy awards were the nominees for, lo and behold, costume (Anna Karenina‘s Jacqueline Durran), make-up and hairstyling (Les Miserables‘ Lisa Westcott and Julie Dartnell), original song (Adele for “Skyfall”) and Andrea Nix Fine for her documentary short. Granted, much like I have long argued with direct attention to the director category, the Academy can only reward what Hollywood gives them, but it’s interesting nonetheless and you’re free to take the information as you will.

When the issue comes to the Australian industry?

I don’t know.

I don’t claim to know.

I shouldn’t have to know because there shouldn’t be an issue. But there is. There always is.

The conversation about female representation within the film industry frequently raises its ugly head. It did so most recently upon the release of FilmInk‘s “2o Most Powerful People in Australian Film” issue and the ensuing drama it created on Twitter and beyond. I’m not here to critique the well known magazine’s standards since I understand what their intentions were, however curious it is that a man such as Justin Kurzel can make it on to the list with only one finished film credit to his name, while plenty of incredible female directors with more could not. Still, as I said, that’s not why we’re here.

I’ve long believed that my home country’s industry was a bit more progressive than America’s. For instance, our homegrown annual awards formerly known as the Australian Film Institute Awards recognised their first female director winner way back in 1979 with Gillian Armstrong for the classic My Brilliant Career (which I felt made an apt banner image up top, don’t you think?) A further seven have won in the years since from 28 nominations. While I didn’t tally the exact figures, there is a similar representation in screenwriting categories, too.

And yet still it’s an issue. There’s little denying that women’s place in the local industry is marginally better than it is in America, but there’s obviously still a ways to go. For instance, as much as I’d love to assume Elissa Down has been developing a masterpiece since her breakthrough in 2008 with The Black Balloon, two episodes of Offspring seems an awfully slim follow through for an AFI-winning director and writer. Likewise Cate Shortland who took eight years to follow up Somersault with Lore in 2012 (for which she won numerous awards around the globe and decent-sized USA box office returns). Meanwhile Jocelyn Moorhouse has been faced with development hells on projects, and the aforementioned Gillian Armstrong has reverted to predominantly documentary work. Funding and development isn’t just a female director problem, obviously, but I wonder if they’re being as encouraged as, say, Morgan O’Neill who directed Solo and Drift and has been given the reins of a $15mil production based on the life of legendary writer Banjo Paterson.

Nevertheless, I didn’t want to write this piece to add another 1000 empty words of woe onto an industry that has seemingly seen the roof cave in these past six months (2013 will not go down as a great year for Australian film, but 2014 is looking up, up, up!) Instead, I wanted to highlight some names within the Australian film and television industry who have not only “made a name for themselves” (a silly term, but we’ll run with it), but who also have a very proven history of getting. shit. done. I doubt if you combined one of the producers below with one of the directors that a funding body would reject it, but I guess you never know. Getting greenlit is tricky business.

It was all relatively simple, actually. All I did was peruse the last few years of AFI/AACTA nominees (and added a few extras that I thought deserved mention) and came up with these 25 women who are shining examples of what can be achieved by women. I think it’s important to know names like these because oh so often I read an article bemoaning the lack of women in the industry without having taken the time to give prominent praise to those that are there doing their job day in day out. By all means, I don’t mean this to sweep the issue under the rug, but instead I mean it to be a positive beacon, a shining of lights onto people who get easily forgotten in the rush to be as negative as possible (as well as some very famous ones). These names are in alphabetical order and we’re not looking at people involved in organisations like Screen Australia or Film Victoria. Just producers, directors, actors, and writers who work hard to get their product on the screen and with the diminishing of quality between cinema and television, is there any shame in working in one medium over the other any longer? I don’t think so!

Imogen Banks (producer, writer)

Imogen Banks only has four series to her credit, but they are Dangerous, Tangle, Offspring, and Puberty Blues. She is very clearly a name to watch. She also wrote episodes of the latter three, and the acclaimed Paper Giants: The Birth of Cleo.

Cate Blanchett (actor)

I’d be lying if I said I didn’t wish Cate Blanchett would make a film back home again – her last was Little Fish in 2005 for which she won an AFI Award – and, hey, maybe there’s an adaptation or two to be made from her years behind the Sydney Theatre Company. Still, she routinely flies the banner for Australia, returning frequently to present at local award shows and to help open events. Her Oscar (for Martin Scorsese’s The Aviator), just by the way, is able to be seen at the permanent “Screen Worlds” exhibit at the Australian Centre for the Moving Image in Melbourne.

Rosemary Blight (producer)

FilmInk’s piece saw fit to include Rosemary Blight at no. 16 based on her heading of Goalpost Pictures. They were the primary producers behind hit The Sapphires, as well as Clubland, and she was also involved in Teesh & Trude, Panic and Rock Island, the Lockie Leonard television adaptation, and Matthew Saville’s upcoming Felony, perhaps my most anticipated Aussie film on the schedule.

Mimi Butler (producer)

Blue Water High, Rush, Howzat!: Kerry Packer’s War, Paper Giants: Magazine Wars. Yeah, I’d say Mimi Butler is on a role in bringing successful projects to the screen.

Jane Campion (director, writer, producer)

An international career that hops between Australia (she brought Bright Star to local shores as a co-production with many locals on board), New Zealand (recent miniseries Top of the Lake was originally an Australian production until ABC backed out due to creative differences), the USA, and the UK. Apart from her high-profile works she was also a part of Soft Fruit, worked on the Aurora screenwriting committee that helped bring Somersault to the screen, and helped push Julia Leigh’s Sleeping Beauty to Cannes and beyond.

Michelle Carey (festival director)

As the artistic director of the Melbourne International Film Festival, Michelle Carey is responsible for the biggest and the oldest film festival in Australia. Pretty impressive, no? Also impressive is that MIFF, now over 60 years old and currently on right as I type, also features a film development fund, a female CEO and board chairperson not to mention a staff roster with many other female positions including operations, programming, marketing, publicity, and industry.

Jan Chapman (producer)

Jan Chapman has long been associated with Jane Campion on The Piano and Bright Star, and Cate Shortland with Somersault and The Silence. Has also helped produce Lantana, Suburban Mayhem, Griff the Invisible, and has the upcoming The Babadook, which is (ding ding ding) directed by a woman, Jennifer Kent.

Penny Chapman (producer)

Penny Chapman is not only associated with Blue Murder and Police Rescue, but has also worked on The Slap (which sold big internationally, I believe), The Straits, and My Place.

Kirsty Fisher (writer)

Kirsty Fisher has written for Dance Academy, H20: Just Add Water, House Husbands, Winners and Losers, and Laid, for which she is also a producer.

Emma Freeman (director)

One of the most acclaimed and respected directors, Emma Freeman has steered clear of feature films, but made a name for herself on series The Secret Life of Us, Puberty Blues, Tangle, Miss Fisher’s Murder Mysteries, Rush, Love My Way, and Hawke, for which she won an AFI Award.

Claire Henderson (producer)

As executive producer on The Saddle Club, Claire Henderson helped produce a show that sold big time (TV and DVD) to basically any continent that has horses. So that’d be… all of them? At the ABC she’s also responsible for Blue Water High, Round the Twist, and The Ferals at one time or another.

Anita Jacoby (producer)

The ABC’s Wednesday night line up was enviable for a while to even the three big networks. Anita Jacoby worked on several of them including the Gruen franchise and Hungry Beast. Has predominantly worked for Andrew Denton’s former company, I believe, on projects like Can of Worms, God On My Side, and one of the world’s first crowd-funded films, The Tunnel.

Claudia Karvan (actor, producer, writer)

Predominantly known as an actress – she’s my personal favourite local TV actor – on such seminal programs as The Secret Life of Us, and Love My Way, Claudia Karvan also spearheaded the latter as a writer and producer as well as Spirited on which she also wrote and produced. A highly respected actor, she’s currently appearing in Puberty Blues and The Time of Our Lives.

Asher Keddie (actor)

A fellow film critic friend has said that he reckons Asher Keddie is the only Australian actor who could get people to go and see a local film purely on their selling power. And, yes, she has the Gold Logie to prove it. Given the giant success of Offspring and Paper Giants: The Birth of Cleo it’s hard not to agree. She’s also been on Love My Way, Rush, Hawke, Curtin, and even smuggled out a role in Wolverine.

Robyn Kershaw (producer)

Originally a casting director on Children of the Revolution and Looking for Alibrandi, producer Robyn Kershaw’s work as producer straddles film and television. She has been involved with Kath & Kim and The Shark Net on TV and Bran Nue Dae, Looking for Alibrandi (as a producer alongside casting), and Save Your Legs! on the big screen.

Nicole Kidman (actor)

Much like Cate Blanchett, yes Nicole Kidman is seen predominantly as an American star now, but lest we forget she does show support for the industry and made Australia even in the face of that screenplay to prove it. I would love to see her use her production house, Blossom Films, which produced Rabbit Hole, maybe make a film to two in Australia. Maybe if she reads this (nudge wink, you’re a goddess) she might she inspired. She returns with The Railway Man this year, an Australian-UK co-production, which has been given a plum spot on the release schedule.

Deborah Mailman (actor)

Australian acting royalty, and perhaps the most popular and respected indigenous actor (give or take a David Gulpilil) of all time. Seems to win award nominations for everything she does - The Secret Life of Us (who didn’t fall in love with her as Kelly Lewis on that groundbreaking series?) Radiance, Bran Nue Dae, The Sapphires (currently an arthouse hit in America), Offspring, Mabo, Mental and so on – and with a staunch desire to tell indigenous tales on screen like Rabbit-Proof Fence, Redfern Now, and Black Chicks Talking. She’s a force in the industry without a doubt. I’d be curious to find out if she has ever been offered the solo lead in a series. I think she’s popular enough to make it a hit, but I also like having her in films so maybe not.

Natalie Miller (distributor, exhibitor)

A fixture of the Melbourne cinema scene, Natalie Miller is the originator and leader of Sharmill Films (a company that most recently released Joss Whedon’s Much Ado About Nothing) and was first the first independent female distributor in Australia. She is also the co-founder of Cinema Nova in Carlton, arguably the premiere destination for exclusive arthouse releases in the state. For what it’s worth, the Cinema Nova were the only cinema to play Sofia Coppola’s The Bling Ring.

Cherie Nowlan (director)

After breaking out with the Brenda Blethyn-starring Clubland (aka Introducing the Dwights in America), Cherie Nowlan moved predominantly into TV in Australia and then America. All Saints, Packed to the Rafters, Dance Academy, and Underbelly are the biggies, and then Gossip Girl, 90210, and new 2013 series Mistresses in the Hollywood. Now there’s a name that many wouldn’t know about and yet should have a photo up in filmmaking school around the country. What Aussie director wouldn’t want those gigs? If they say “no” then they’re probably in it for the wrong reasons.

Jacqueline Perske (producer, writer)

Having developed a strong working relationship with previously mentioned Claudia Karvan, Jacqueline Perske has worked on Love My Way and Spirited as a writer and producer, The Secret Life of Us as a writer, and even received AFI, IF, and Film Critics Circle nominations for her screenplay to Little Fish, which starred Cate Blanchett.

Daina Reid (director, actor)

This lady right here seems to have a monopoly on all the really big TV series, movies and miniseries, doesn’t she? The Secret Life of Us, MDA, All Saints, Satisfaction, Very Small Business, City Homicide, Bed of Roses, both Paper Giants films, Offspring, Rush, Howzat!: Kerry Packer’s War, Miss Fisher’s Murder Mysteries, and upcoming Nowhere Boys. Not to mention feature film I Love You Too, and a very accomplished career as a comedian and actress on Full Frontal, Jimoin, The Micallef Program, Kath & Kim, and Welcher and Welcher. Yeah, I’d say Daina Reid’s going pretty darn well and shouldn’t be in any danger of losing out on jobs any time soon.

Julie Ryan (producer)

While Julie Ryan’s credits on Red Dog and 100 Bloody Acres (already on screen and VOD in America) are keeping her going at the moment, what I find most impressive is her roster of Rolf de Heer films. Having worked as producer on most of his titles since The Old Man Who Read Love Stories in 2001 (arguably his hardest production) and an ability to pluck funds out of thin air for Dr Plonk and Ten Canoes shows determination and skill. I’d want her on my team. Plus, she has Tracks premiering at the upcoming Venice Film Festival with Mia Wasikowska and Adam Driver (Girls).

Liz Watts (producer)

She could argue her position on any list such as this (or FilmInk’s on which she was ranked no. 15) based on one film: Animal Kingdom. She steered that film to instant Aussie classic status, which spun into an unlikely but well-deserved Oscar nomination for star Jacki Weaver. Other than that, she has TV series Laid, and other features Lore, The Hunter, Walking on Water (a very touching AIDS drama), The Home Song Stories, and David Michôd’s Animal Kingdom follow-up, The Rover starring Guy Pearce and Robert Pattinson. Yes, yes. Deserves big thumbs up for getting Michôd to stay in Australia for his sophomore effort.

Joanna Werner (producer)

As a producer on H2O: Just Add Water and Dance Academy (on which she’s also a writer and co-creator), Joanna Werner has been involved in two programs that have found sales and cult followings in America, which is money. There was talk of a H2O movie, but I haven’t heard anything about that in quite some time, sadly.

Kate Woods (director)

See also Cherie Nowlan. After winning an AFI Award for directing Looking for Alibrandi one could mistake Woods for having fallen out of the industry. She actually went into television, directing the Changi miniseries in 2001 and moving to America to director episodes of Without a Trace, Law & Order: SVU, and Private Practice. Lately she’s working more than ever on NCIS: Los Angeles, House, Bones, Castle, Hawaii Five-O, Suits, and was most recently given the big honour of directing an NBC pilot (Aussie-made, US-set Camp with another big Aussie female name, Rachel Griffiths).

And then there are people like Catherine Martin, Mandy Walker, Jill Billcock, Cappi Ireland, Melinda Doring, Veronika Jenet, Sarah Bortignon, and so many, many more who work in fields like sound and design that have no problems getting work. Although Walker does work in a field that’s notoriously man-centric (that’d be cinematography). Martin has the potential to become Australia’s most successful Oscar winner with her work on husband Baz Luhrmann’s The Great Gatsby.

So, there you go. 25 names (and then some) of Australian women in the film and television business that deserve not just credit for their achievements, but actual prominent recognition. We’ll never get anywhere if those who are out there making the stuff we watch aren’t celebrated and cheered on. Not in a patronising “you go, girl!” kind of way, but in a professional, respectful way. I so frequently hear that women tend to give up ambitions of working in this industry because they so rarely see role models, but maybe lists like this and any others people would care to write can show that it’s very much possible to work in this industry and be a woman and do it successfully, too. Otherwise we’ll just keep getting op-eds about what a “cockforest” (term courtesy of one of this list’s inspirations, critic friend Mel Campbell, via Ben Law at the ABC) it all is and it’ll be little more than a vicious circle of sexism.

And if you’re also interested in female film critics? Again, they aren’t as many as there are male critics, but there are many great ones. How about the aforementioned Mel Campbell (The Thousands), Tara Judah (The Saturday Magazine, Plato’s Cave), Cerise Howard (Smart Arts, Senses of Cinema), Lesley Chow (Bright Lights), Jess Lomas (Quickflix), Alice Tynan (all sorts), Philippa Hawker (The Age), Rebecca Harkins-Cross (The Big Issue), and so on.

I know I and many others would appreciate your assistance in spreading this list around and, by all means, adding to it. These were just 25 I found; I know there are more.

And, yes, I do hope you’re singing the title of this blog to the song from The Sound of Music. Even if I’m not a fan of the movie.

![mybrilliantcareer]()

Image source 1 //

Conjuring the Ultimate Fighting Champion of Haunting Movies

This review contains some spoilers to The Conjuring.

James Wan’s The Conjuring is the Ultimate Fighting Champion of haunting movies. It is all of the movies. Every single one. Coming to the film several weeks after its phenomenal box office, I was at least somewhat viewing it in a way where I was trying to seek out what it was about this movie that had attracted so much. These type of movies are a dime a dozen – the coming attractions beforehand can show you that – hell, the director has another one of his one, Insidious: Chapter 2, out in just a couple of months! But most of all, as a fan of the genre, I just wanted to see something scary and fun. Watching it though was like experiencing a crash course in haunted houses. As these movies go, it’s an epic.